Faster, Please! — The Podcast #31: Radical Life Extension and the Silicon Valley Quest to Cure Death

July 14, 2023

Welcome to Faster, Please! — The Podcast. Several times a month, host Jim Pethokoukis will feature a lively conversation with a fascinating and provocative guest about how to make the world a better place by accelerating scientific discovery, technological innovation, and economic growth.

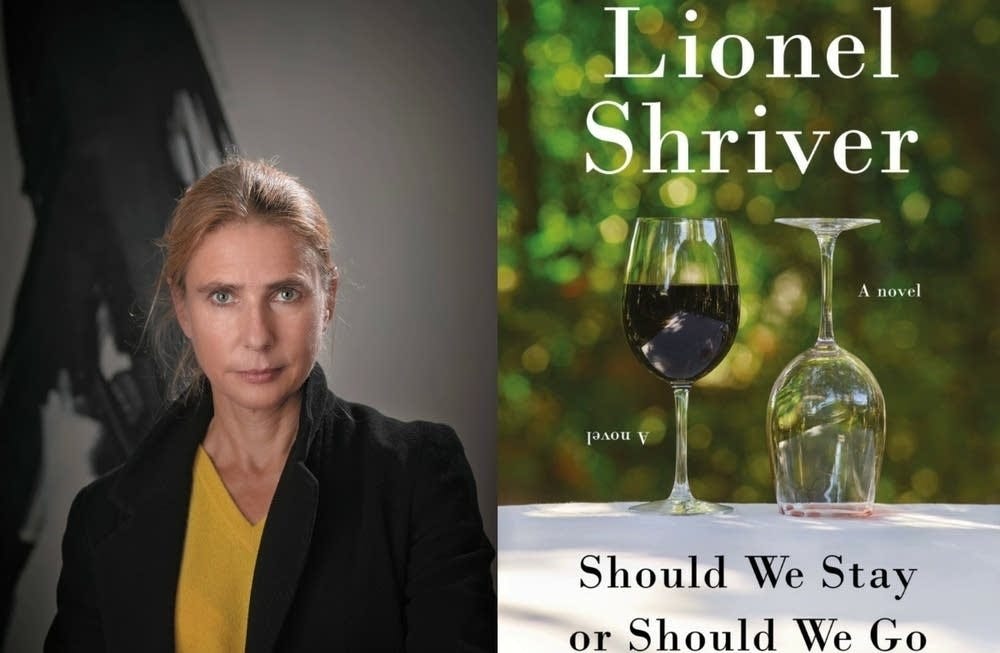

“The promise of eternal life has conventionally been the dangled carrot of religion. It is now the holy grail of Silicon Valley,” writes novelist Lionel Shriver in a recent National Review cover essay. In this episode of Faster, Please! — The Podcast, Lionel joins me to discuss why some tech billionaires are chasing after immortality and the serious challenges that would accompany extended human lifespans.

Lionel is a columnist for Britain’s Spectator magazine. Her books include We Need to Talk About Kevin and Should We Stay or Should We Go.

In This Episode

- The promise and peril of immortality (1:11)

- Storytelling and optimism (6:44)

- Lifespan vs. healthspan (12:23)

- Post-humanity (19:19)

Below is an edited transcript of our conversation

The promise and peril of immortality

James Pethokoukis: In the National Review essay, you make it clear you are not a medical expert, you’re not a research scientist; you’re a writer of fiction. Of all the things you could have written about, both as an essay and also in your book, Should We Stay or Should We Go, what originally created your interest in this topic of longevity?

Lionel Shriver: I should also clarify that, for someone who’s writing about life extension, I am not immortal either. So I have no qualifications for this aside from having applied myself to it imaginatively. The book you mentioned, Should We Stay or Should We Go, is a novel about a couple that has vowed to kill themselves once they both reach the age of 80 because they don’t want to fall apart. They don’t want to burden others with their own crumbling. It’s a parallel universe book that explores any number of different futures for this couple. And one of those futures is why I suspect I was approached to write this essay for National Review, and it’s one in which there’s a cure for aging. Basically, my characters live forever. Everyone in the world looks 25 and they never look any older. I have addressed myself to what that future might look like and not just look like, but feel like. What would it feel like to address yourself to a future that was potentially infinite?

In the novel, it starts out great. It was exhilarating to watch your spouse, rather than get older and older, get younger and younger and return to the age when you fell in love. And everyone is healthy. There are no limitations anymore. And all your choices are also potentially infinite. You can try out every profession. It’s no longer a matter of, what are you going to be when you grow up? You can be whatever you want, and then you can change your mind. It’d be something else. You can move to any city. All your choices are just this kind of smorgasbord of what you might sample. And that seems fun to begin with.

That sounds like a near-utopian scenario.

Yeah. The trouble is that when you think about it, one of the things that gives our lives urgency is finitude, that our decisions matter because you can’t undecide them. The way we choose to spend our time matters because there’s a limited amount of it. There’s no redo. And effectively with eternal life, there is a redo. There’s infinite redo. You can just go back and do something else. You can just go in a different direction. If you marry the wrong person, you can just marry someone else and you won’t have given them, say, 10 years of your precious life. I mean, yes, but there are so many years left that it doesn’t matter. And the trouble is that once you remove that, then nothing seems to matter. And that is depressing. When you remove that urgency, you also potentially remove meaning. And everything becomes arbitrary.

One of the things that happens to my characters is their characters start to decay. In some ways, they trade places in terms of what kind of person they are. The wife has always been the more optimistic and reflective and joyous, whereas her husband was more programmatic and more of an ideologue. And as the hundreds of years go by, he becomes much more himself reflective and philosophical and she becomes impatient and misanthropic. Because character itself becomes arbitrary. In the essay, I’m trying to look in a nonfiction sense at, what would it really be like both emotionally and practically to have a permanent human population? And that raises huge practical problems, too. Like, you don’t have any children anymore. You can’t.

Storytelling and optimism

Is it easier for you to come up with the more dystopian scenarios? Oftentimes, I’ll criticize sci-fi writing, television, books as overly focused on the dystopian. It’s almost like a lack of effort. In this case, is that basically justified: that it’s very hard to write a scenario where everything kind of turns out okay if people are living forever?

It is hard to write. It’s always hard to write positively. It’s hard for me even to write characters that are purely lovable. Since I don’t know any. And it’s hard to write happy endings. I do write happy endings, but they’re hard to get there. And I feel you have to earn them. You can’t just have happily ever after and that’s it. There is one chapter in Should We Stay or Should We Go which is purely positive. It’s called “Once Upon a Time in Lambeth,” which is the neighborhood in London where they live. And it’s the perfect old age. It’s what we would all want. They grow only more physically beautiful as they age until people are stopping on them on the street wanting to take their pictures or paint their portraits because they’re so striking. They grow only more in love and they have only a better sex life. It gets more and more rich and imaginative and exciting. Young people admire them because they both started second careers and had become hugely successful. And young people flock around their dinner table and want to hear their wisdom. Meanwhile, outside in the rest of the world, the Israeli-Palestinian problem is solved at last, Africa is a thriving economic power, etc. The thing is that there’s a point only a few pages into this particular chapter that you get it: This is a satire. This is the one scenario that won’t happen.

It’s almost so ridiculously…

It’s ridiculous. In fact, it’s hilarious. Optimism can be funny. And in some ways, it’s also an illustration of kind of a fictional problem. Because without bad things happening, there is no story. And what makes that particular chapter a story is your growing consciousness that this is not possible. That this is ridiculous. That you are being made fun of, basically, because this is what you want and, you know, give us a break. You’re never going to get it. This is hilarity at your expense. I am sympathetic with your frustration with science fiction. And it’s not just science fiction. Literary fiction has a lot of unhappy endings and tragedy and dysfunction in it. That’s the nature of story. It’s a requirement. No badness, no story. The genres vary in terms of what that scale of badness is going to be and whether or not it’s eventually going to resolve into something more palatable. But fiction is by its nature about disaster.

Would your critique be the same if instead of talking about living hundreds of years, our lifespan was doubled? Instead of everyone living to be at least, on average, 75, 80, 85, it was 150, 175.

To a degree. Though I think that issue of urgency, of how you spend your time, once you bring it down to, for argument’s sake let’s say 150 years, that’s probably less of an issue. But the practical problems do become more intrusive. If we’re all living to 150, then we are going to have a huge elderly population and hardly any young people. And that poses a lot of economic issues. One of the things that I posit in the essay is that living substantially longer means the end of retirement. You can’t live to 150 and retire at 65. It’s economically impossible. So that means working for a long time. And the irony of this whole discussion, of course, is that the real problem we are facing is people living too long. People living too long in terrible shape. That’s the real economic crisis.

Lifespan vs. healthspan

In that National Review essay, you write that you’re more interested in expanding the human healthspan than the human lifespan. Extending our healthy years but not necessarily delaying death seems like a very different project.

Yes. And I try to make the distinction between different projects. A lot of the Silicon Valley people are looking at longevity from the perspective of, “Let’s cure death. Let’s basically try to live forever.” But a much more modest group of people, and more practical, are looking at not necessarily living any longer, but living well longer. And I’m very sympathetic with that project. I’m like anyone: I don’t fancy falling apart, and I would rather keep my wits about me and still be able to totter out on the tennis court and then preferably drop dead on the baseline one day. And that would be that. That’s a laudable goal. And if we can get closer to that, we’d save ourselves a fortune.

When we talk about the Silicon Valley quest to cure death, does this really all come down to a fear of death by people who maybe don’t hold traditional religious views of the afterlife? Or do they want to live longer so they can, I don’t know, start more companies? What’s the motivation here?

I drew that distinction in the essay. There are two different things that might motivate you to extend life as long as possible. And one of them is clearly fear of death. We don’t know what happens. I have my suspicions — you’re not there anymore. And it’s possible that the actual experience of death is not that bad, although the lead-up can be pretty grim. But the other thing that might motivate you is appetite, is desire, is wanting more. And that is something I am sympathetic with. I admire people who generate enthusiasm for living, for everything that it offers, for relationships, for love, even for another good glass of red wine. That is a positive motivation for this kind of research, which is going on all over the place. There’s a lot of money being thrown at it. And I admire that. I think one of the questions you have to ask yourself in this whole life extension thing is, how much appetite would I have for continuing to be here? How many years does it prospectively give me joy to get up in the morning? And what would I be looking forward to? Is there any point at which you’ve just had enough red wine? (A prospect I find almost unfathomable.)

If we’re looking at a civilization where people are living longer and it’s richer, we’re solving all these other problems and we’re heading out to the stars, it seems to be like there would be a lot to be curious about. There would be a lot to see and do, and I’d hate to miss it. I’d hate to miss all this really great, cool stuff by only living to 90 years old.

There’s another chapter in which my couple, as in most of these chapters to keep the story going, do not kill themselves when they’re 80 years old. They live to well beyond 100 in relatively decent shape. They’re okay, but the rest of the world isn’t. Basically they live to see the end of Western civilization. This takes place in Britain. Britain has become completely overwhelmed with migration from Africa and the Middle East, which by the way demographically is very likely and is already happening. Meanwhile, there’s a homegrown anarchist movement, because young people see no future for themselves; the place is in a state of economic collapse. They burned down parliament and they’ve shredded all the pictures in the National Gallery, etc. Basically, Western civilization is over. And the question that chapter asks, as the house they live in is invaded by migrants and taken over and they’re exiled to the attic and basically eating dog food, if they could roll back the clock, would they like to live to see this or not?

And I think that’s an interesting question, because the way you describe the future as you see it, which inspires your curiosity, is more inventions, space travel, all these wonderful, fascinating things happening. Well, you know what? More than wonderful, fascinating things happen; things fall apart. And I have great difficulty on my own behalf answering the question that chapter poses. And the couple disagree. One of them would have been happier to die earlier and not see this. And the other one is so interested in the story that they’ve been involved in. And of course, if you’re a news reader especially, you’re involved in all kinds of stories all the time. I certainly am. And one of the sacrifices of dying is not finding out how some of them end. But the other one is so interested in the story that even if the ending is dark, he’s glad to see it because he wants that narrative appetite to be satisfied. To me, that’s one of the biggest questions on longevity. Do you want to stick around if the world takes a serious turn south? Do you want to stick around for that?

Post-humanity

The political scientist Francis Fukuyama has written about what he calls our “post-human future.” If death is an important and intrinsic part of our humanity, then immortality or near immortality moves us to being something that is no longer human as we know it. And because liberal democracy is built on the idea of human equality and a connectivity among humans everywhere, through all time, he worries about life extension or other enhancements undermining that equality. Does that concern you?

Well, to a tiny degree, we’ve already got that differentiation based on economic profile, which does partially determine your life expectancy. People in Western countries who are themselves well off are likely to live substantially longer than either people outside Western countries or people within Western countries who are poor and generally in worse health. So we are not quite the same already. We’re not looking at the same lifespan. One of the other things I did address is the likelihood that should these longevity efforts be availing, the chances are extremely high that they would be expensive and therefore available to the elite and only the elite. And therefore, that kind of division that we’re living with already would grow greater. And I posited that it was not impossible that the resentment on the part of the lower classes could become homicidal.

I think if you’re really talking about effectively evolving into a slightly different species, then you would be generating a huge amount of political tension. And also you’d create this sense — and this is the kind of thing that science fiction explores all the time — of an overclass and therefore a kind of overlord class that lives very much longer and is likely to be hoarding the wealth and living remotely from everyone else. And I think that’s more likely than the elite uploads themselves to robots or a computer. When you were talking about the nature of humanity, what it’s like to be a person: I find the disembodied versions of a human future unlikely. Were we ever to achieve it, that’s where we would really part ways with the species as it has always been.

We experience the world in bodies and therefore we have all these senses and vulnerability to physical injury and disease. We have a very complicated relationship to our bodies, which I’ve written about at length. It’s of great interest to me. And therefore, if we were in robots that you whose injured arm, you could simply screw a new one on — much less if we were in some kind of jar, effectively, like those brains in a jar in 1950s sci-fi movies — that never seems enviable, does it? To no longer have the embodied experience. The embodied experience comes with a lot of pain, but it also comes with a lot of pleasure.

Are you optimistic, meaning that you think this research is going to pay off in dramatically longer lives, whether or not it’s immortal? People are taking this very seriously. Again, we have researchers who’ve said someone who might make it to 150 has already been born. Do you think, directionally, this is happening and we need to be talking about it seriously now and thinking about it seriously?

There’s never any harm in thinking about anything. And it’s interesting, so yes. My main concern would be further progress in, strictly speaking, extending longevity but not making enough progress on that business about extending healthspan. And then you’ve just got a bigger problem on your hands. So that, great, you’ve got a bunch of people who are 125 and they’re drooling and don’t remember their own names. This is not a future that we should be looking forward to — not personally and not socially. It’s that health span thing that I think that we should be focusing on. And that means concentrating especially on dementia research, continuing to improve joint replacement. (I keep waiting on replacing my own knees, which are a complete wreck, because I just want them to inject some stem cells in them and not carve them out.)

We should be focusing on medical technology that will improve the experience of being older, rather than just make people technically able to get older. And I do think a certain amount of deliberateness here as to where you put your resources is merited. I wish that drug that the FDA just approved did better than delay dementia by five months, for example. That’s a start, but it’s kind of discouraging. It’s so small. I personally am not planning on devoting the rest of my life to living as long as possible. There’s a kind of circularity to that or an implicit pointlessness. I want to spend what time I’ve got doing something else rather than just trying to stick around a little bit longer. So while I get my exercise and I try to eat sensibly, I’m not going to be one of those people who is totally obsessed with diet and a

A million dollars a year on this infusion, this transfusion…

Right. Some of these people: This is what they spend all day doing. There’s one guy who gets regular transfusions from his own 17-year-old son. He obviously spends hours and hours every day at his exercise regime. He takes hundreds of supplements. (I foresee acid reflux.) I’m not going to do that. If that means that I take five years off my life expectancy and get to do something else and finally finish the last series of Succession, I’ll take that. I’ll take short and sweet.

Sign up for the Ledger

Weekly analysis from AEI’s Economic Policy Studies scholars